DANGEROUS PLACARDING

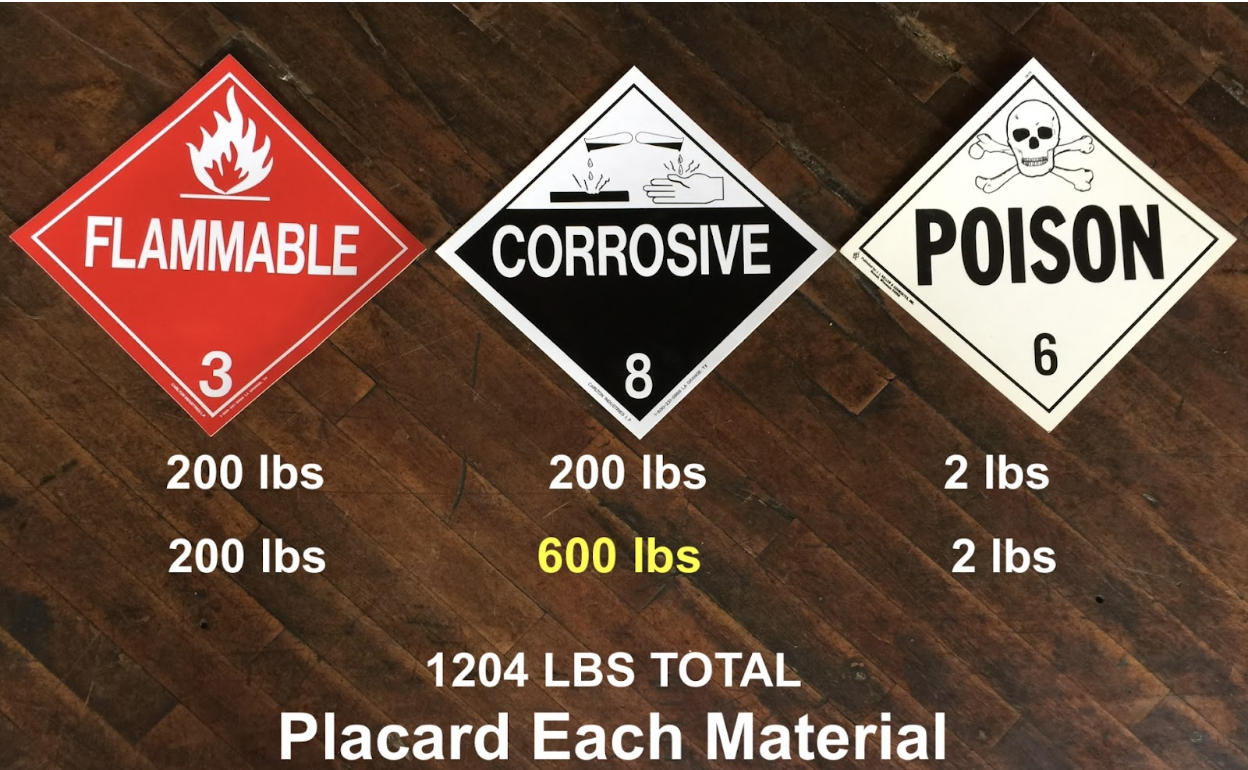

When loading 200 pounds of Flammable Liquids, 200 pounds of Corrosive Liquids and an additional 2 pounds of an Oral Poison, on a transportation vehicle, shippers and generators are not required to provide placards as the aggregate gross rate is only 402 pounds. Well, below the 1,001 pound gross weight table 2 non-bulk placarding requirements, in 172.504(c) therefore, excepted from Subpart F of the DOT 49 CFR Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration,(PHMSA) Hazardous Material Regulations (HMR).

THE“ NON-BULK TABLE 2 DANGEROUS PLACARD”

Considering that most trailers have one or at the most, two placard holders, once drivers exceed the 1,001 pound limit, there is an exception in 172.504(b) for these three separate materials that require placarding. The Dangerous placard can be used in this situation, to alleviate the need for additional placarding holders.

Two or more hazardous materials requiring different placards specified in Table 2 may be placarded with the Dangerous placard in place of the separate placards specified for each of the materials in Table 2. Solving the problem of not having more than one holder on the truck or transport vehicle.

HIDDEN DANGER

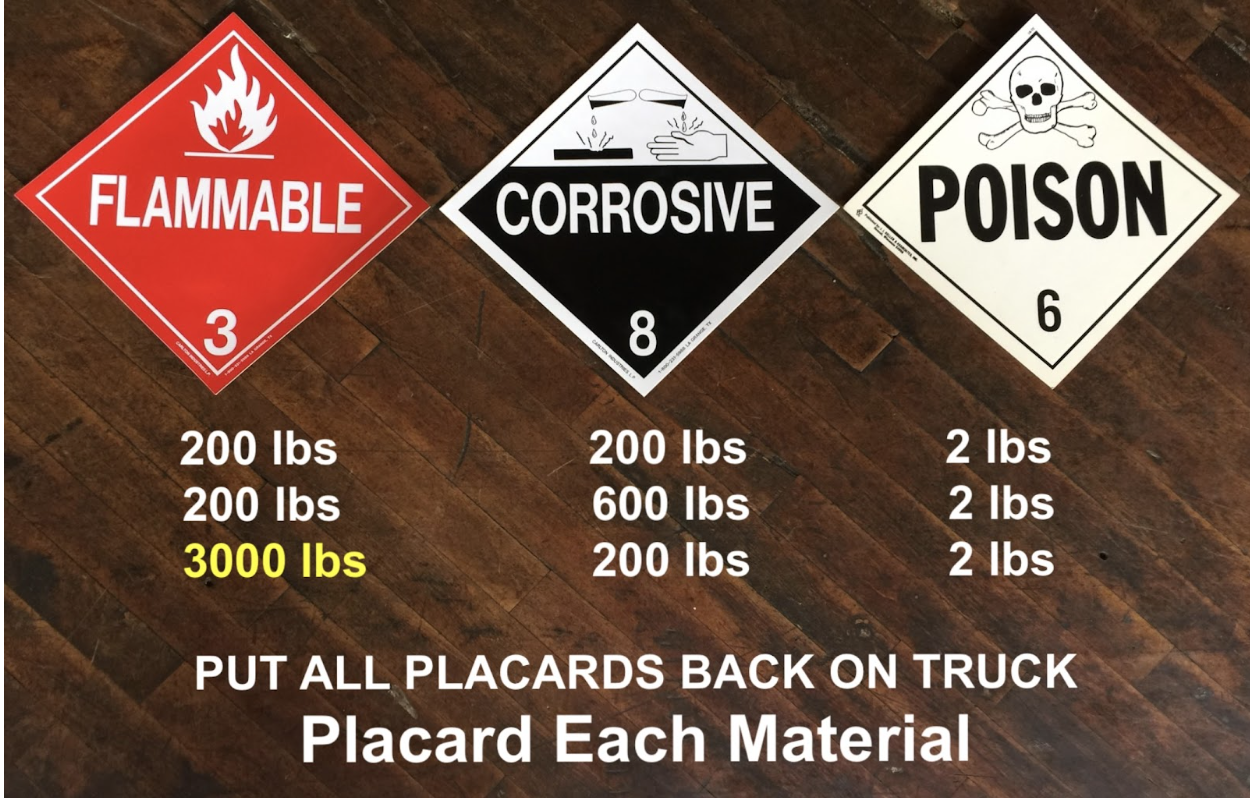

However, when “1,001 kg (2,205 pounds) aggregate gross weight or more of one category of material is loaded therein at one loading facility on a freight container, unit load device, transport vehicle, or rail car, the placard specified in Table 2 in paragraph (e) of this section for that category must be applied”.

UNFORTUNATELY

So, a situation could arise at the next pick up, if the driver accepted over the 2,205 pound limit of one material. In this case 3,000 pounds of a Flammable Liquid in addition to 200 pounds of Corrosives and 2 pounds of Oral Poison.

I believe two placards would still only be required in this particular situation.

It seems to me only the Flammable Liquid placard would be required. The other two would still be covered under the Dangerous placard at least until they, the corrosive and the poison, individually exceeded the 2,205 pounds.

EXCEPTIONS

Non-bulk packagings containing only the residue of a hazardous material in Table 2 are not covered by Subpart F. In addition this vehicle with all three separate placards displayed, though not required, at only 402 pounds would still be within the confines of the HMR.

FEWER EXCEPTIONS

Bulk freight containers, unit load devices, transport vehicles and rail cars, should be placarded on each side and each end with the placards specified in table 2. Table 1 materials placard, regardless of container capacity. Exceptions and substitution placarding, like the use of Class 9, Miscellaneous Hazardous Materials placards, never, including others, are found in 172.504(f).

You're not out of the HMR when a vehicle has less than 1,001 pounds of table 2 non-bulk containers, you're just out of Subpart F, the placards. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations,(FMCSR) under the Commercial Drivers License,(CDL) Regulations in Section 390.5 under the definition of “Commercial Drivers License” cites hazardous material placarding requirements as one of 4 CDL triggers, hence the confusion.

Be Safe!

Robert J. Keegan

President and Publisher

Hazardous Materials Publishing

Transportation Skills Programs

610-587-3978 (cell- text)

610-488-9013 (home)